Many land owners who want to develop their property run out of money before their property development project is realised.

Some land owners find an investor who is prepared to fund the development, not as a lender who receives interest, but as a joint venturer who partners with the land owner and shares the development profit.

The relationship is documented as a joint venture for property development.

The recent decision of the Supreme Court of New South Wales of Coleman v Hart-Hughes [2017] NSWSC 656 (Darke J) illustrates how investor should protect their investment in case the joint venture relationship sours, as it did in that case.

How the joint venture was formed and performed

Ms Hart-Hughes (the land owner) owned a semi-rural property at Bangalow of 3.56 ha. She wanted to subdivide the property to take advantage of a recent re-zoning by the Byron Shire Council. But she had no funds to carry out the development because she had exhausted her borrowing capacity: she owed $1,650,000 under the first mortgage and $190,000 under the second mortgage. In fact, she was in serious financial difficulty, having defaulted under the first mortgage loan.

Mr Coleman (the investor) agreed to invest funds to clear the loan arrears and to develop the property for subdivision and sale.

They entered into a Joint Venture Deed for Land Development on 4 July 2012, which contained these provisions:

-

The development project was the subdivision and sale of the land, and the development and sale of houses on the land.

-

The land owner agreed to contribute the land at cost (subject to the existing mortgages) and the investor agreed to contribute the funds which were $666,258 (already paid) and $118,475 (to be paid).

-

The land owner and the investor formed a Joint Venture Committee (JVC) to make the joint decisions for the project.

-

The land owner was to act as the project manager.

-

The development profit, after payment of approved budgeted costs (including the land cost), repayment of the mortgage loans and the investor’s contribution, was to be divided and distributed 50% to the land owner and 50% to the investor.

-

he land owner acknowledged that the investor:has a caveatable interest in the Land and will consent to the registration of a caveat on the title to the Land.

The investor registered a caveat over the title.

In February 2016, the subdivision was approved as two smaller lots and one larger lot. The land owner requested the investor consent to the registration of the plan of subdivision. The investor requested details of the amounts owing under the mortgages.

The land owner responded not by giving the details of balances outstanding, but by serving a lapsing notice to remove the caveat. The investor consented to the registration of the plan, and the plan was registered in July 2016.

The two smaller lots – 19 and 21 Ballina Road had houses on them. They were sold – lot 1 for $730,000 and lot 2 for $835,000. The sale proceeds were applied to the first mortgage.

The larger lot had a long frontage to the Pacific Highway, and had development potential/approval for 20 dwellings in five separate two-storey buildings. The prospect of sharing a substantial development profit with the investor goes a long way towards explaining why the land owner wanted to walk away from the joint venture.

The issues in the legal proceedings

The investor instituted legal proceedings in the Supreme Court to maintain the caveat, by seeking declaratory orders that:

-

the land owner had granted a valid equitable charge over the land; and

-

the land stood charged to secure repayment of $881,233.90 payable under the Deed.

The land owner wanted to end the joint venture, arguing that:

-

the joint venture was illegal because only the profits, and not the losses were shared;

-

the joint venture deed had been terminated by frustration.

The Court’s determination on the validity of the joint venture deed

The Court determined that the deed was valid and enforceable for these reasons:

-

A joint venture deed is a contract. There is no statute which makes it illegal to share profits, without sharing losses in a joint venture. Nor is there any public policy consideration – there is no legal wrong, immoral act or illegal purpose which would make it illegal to agree that losses are not to be shared.

-

For a contract to be terminated by frustration, an unexpected event must occur which renders the contract radically different from what was entered into. In this case, delays in the project from 2012 until 2016 were not unexpected and did not prevent the parties from performing their obligations according to the deed.

The Court’s determination on the caveat

The difficulty was that although the deed conferred a caveatable interest and stated that the land owner will consent to the registration of a caveat, it did not specifically state that the land owner granted an equitable charge over the land.

The Court reviewed the Joint Venture Deed and determined that despite no reference being made to the grant of an equitable charge, the investor was entitled to maintain the Caveat:

The terms the Deed do support the implication of an intention that the plaintiff have an equitable charge to secure repayment of the monies he advanced. The Deed does not seem to contain any indication to the contrary sufficient to overcome the implication.

Comments on protection by caveat

In entering into this joint venture, the investor had good reason to leave the land in the land owner’s name instead of transferring the land into a jointly owned entity, namely the mortgages on the land would not need to be refinanced (if indeed they could).

But without the security of being registered on the title, the investor had little control over their investment. While a Joint Venture Committee provided some protection, the investor needed security for the performance of the Joint Venture Deed in the form of a registered caveat.

What the decision of Coleman v Hart-Hughes teaches us is that it avoids argument if the caveat clause specifically states that the land is charged with the performance of the Joint venture.

If so, a registered caveat will protect the investment in a property development project.

And the investor should insist on sharing only the profits, not the losses, from the project.

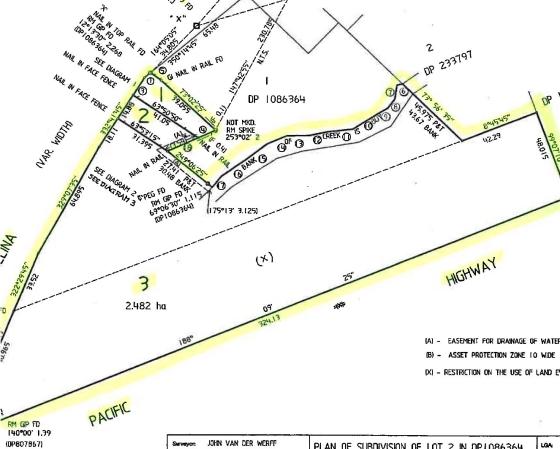

This is the subdivision plan which was registered in July 2016, with the land outlined in yellow.